Tour ideas in Budapest – Exploring Budapest’s Jewish heritage

Budapest is home to one of the most significant Jewish heritage sites in Europe, reflecting centuries of Jewish history, culture, and resilience. The city’s Jewish Quarter, located in District VII (Erzsébetváros), has been the heart of Jewish life in Budapest for generations. Today, it remains a vibrant area, blending history with modernity, offering visitors an insight into Jewish traditions, architectural marvels, and memorials.

Photo: mazsihisz

History of the Jews in Hungary

Among the most prominent landmarks of Budapest’s Jewish heritage are three stunning synagogues: the Dohány Street Synagogue, the Kazinczy Street Synagogue, and the Rumbach Sebestyén Street Synagogue. These buildings tell the story of a once-thriving Jewish community, the hardships it endured, and its ongoing cultural revival.

First and foremost it is important to detail a little bit how their status changed in accordance with Hungarian history. This brief historical overview will help you understand a few important things.

Image: Vízkelety Béla: The march of King Matthias and Beatrix to Buda

The first Jewish settlers arrived during the Roman rule of Pannonia, likely as merchants and soldiers. Some inscriptions and artifacts suggest that Jewish communities existed in Roman settlements, such as Aquincum. (Northern Budapest)

After the Hungarian conquest (895 CE), Jewish merchants settled in Buda, Esztergom, and other trade hubs. Under King Stephen I (1000–1038), Jews were allowed to trade but faced restrictions in land ownership. Two hundred years later, during the reign of King Béla IV (1235–1270) he granted them protections after the Mongol invasion (1241), recognizing their economic contributions. Almost a century later under Louis I (1342–1382), increasing restrictions were introduced, including higher taxes and property limitations. The first “pogroms”, expulsions under Sigismund (1387–1437) but later these were readmitted for economic reasons. Due to peaceful coexistence the Jewish community thrived in Buda, forming a distinct quarter near the royal palace. Surprisingly, greater religious freedom occurred after the Ottoman conquest of Buda (1541). Due to the wisdom of Sulejman I. Jews experienced free practice of religion under Turkish rule. Furthermore, they played key roles as merchants, tax collectors, and intermediaries between the Ottomans and Christian populations. Jewish communities expanded in Buda, Eger, and Szeged, benefiting from Ottoman tolerance of non-Muslim minorities.

After the Habsburg reconquest (1686), Jews were expelled from Buda and faced harsh anti-Jewish laws. Additionally, Maria Theresa (1740–1780) imposed heavy taxes and restrictions on them making Jewish life even harder. The Toleration Edict, (1783) which granted Jews limited civil rights, encouraging Germanization and secular education to them, broke the ice. Families were offered to take up German sounding family names. Usually these were associated with a combination of colors or/plus professions, or mundane things. (Grünwald, Schwarz Muller etc.) By the early 19th century, Jewish populations grew significantly, especially in rural markets and urban centers. Jews were heavily involved in commerce, industry, and banking, contributing to Hungary’s modernization. However, the nation as a whole was heavily suppressed, leading to a revolution. The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 promised Jewish emancipation, and many Jews fought for Hungarian independence. After Austria crushed the revolution (1849), Jews faced renewed discrimination, but by 1867, they gained full civil rights under the Austro-Hungarian Compromise.

The late 19th century was a golden age for Hungarian Jewry, as they became key figures in finance, media, arts, and industry. Budapest became home to one of Europe’s largest Jewish populations, with prominent synagogues like Dohány Street (built in 1859).

Religious schism (1868-69) led to the creation of Neolog, Orthodox, and Status Quo Ante Jewish movements. (We will detail these in the next paragraph). Despite rising antisemitism in the early 20th century, Jewish life flourished, with Hungarian-speaking Jews deeply integrated into society.

After World War I and the Treaty of Trianon (1920), Hungary lost two-thirds of its territory, leading to economic hardship and nationalism. The Numerus Clausus law (1920) (a.k.a. the law of closed numbers) was Europe’s first anti-Jewish quota law, restricting Jewish access to universities, higher education and certain professions. Although Hungary remained relatively safe for Jews compared to Nazi Germany, antisemitic policies grew stronger. Eventually, Hungary allied with Nazi Germany, but until March 1944, Hungarian Jews remained relatively protected. Labor camps were established, but there were hardly any deportations. Sadly, however On March 19, 1944, Nazi Germany occupied Hungary, and the deportation of Jews to Auschwitz began immediately. In less than two months, 437,000 Hungarian Jews were deported, mostly to Auschwitz-Birkenau. The concentration of the Jews continued resulting in the establishment of the Great Ghetto (present days 7th district) in late 1944; thousands perished due to starvation, disease, and Arrow Cross (Hungarian fascist) executions. Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg and Swiss consul Carl Lutz saved thousands of Jews using protective passports or got them out to neutral countries. After the second World War Survivors returned to Budapest, but Jewish life was devastated. Under the Communist regime, Zionist organizations were banned, and Jewish – and any – religious life was strictly controlled. Many Hungarian Jews emigrated to Israel, the U.S., and Canada. Famous Hollywood stars and influential figures have a Hungarian Jewish root. Actors; Tony Curtis, Johnny Weissmuller (Tarzan), Béla Lugosi (Dracula), the wife of the beauty product and cosmetics tycoon Estée Lauder, journalist Joseph Pulitzer, pharmaceutical giant Gedeon Richter to name a few. The 1956 Hungarian Uprising led to another wave of Jewish emigration.

Photo: Szappanos Veronika – The Garden of Silence within the Dohány street synagogue

1989, Budapest’s Jewish community has experienced a remarkable cultural, religious, and communal revival—reclaiming its identity, restoring heritage, and redefining Jewish life for the 21st century. The collapse of the Communist regime marked a turning point. With Hungary’s democratic transition, Jewish life in Budapest began to resurface and reimagine itself. Suddenly, religious freedom, cultural expression, and institutional rebuilding were possible. Today, Budapest is home to the largest Jewish community in Central and Eastern Europe, estimated between 75,000 and 100,000 people, with an active population of about 10,000–20,000 engaged in community life. Today, Jewish life in Budapest is marked by vibrancy and diversity. From traditional Shabbat dinners in Orthodox homes to secular Jewish cultural meetups, from Holocaust education to Hebrew schools, the community is writing a new chapter—rooted in memory, inspired by freedom, and open to the future.

Budapest’s Jewish revival is not merely a return to the past but a reinvention, proving that even after trauma and repression, a community can reclaim its identity with pride, creativity, and resilience.

About the religion

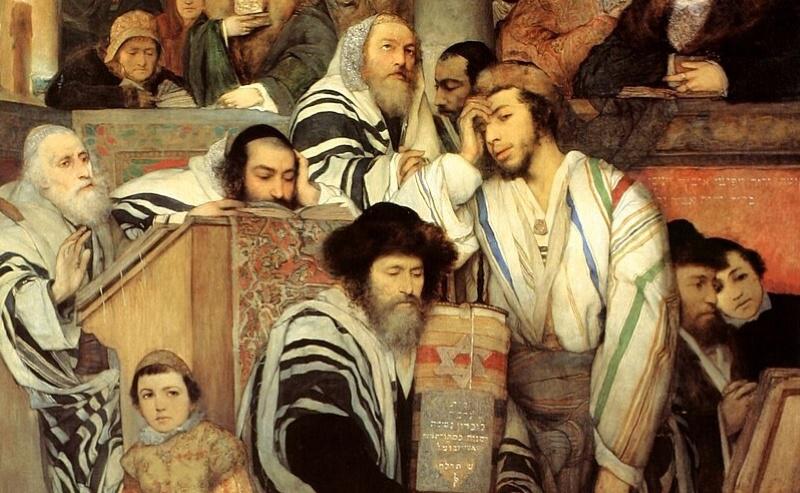

Image: Maurycy Gottlieb – Jews Praying in the Synagogue on Jom Kipur

To fully understand the situation of the Jews of Budapest, we must include a very important topic as well: religion. As we mentioned earlier, we would like to discuss the forms of Judaism present in Budapest from the early 20th.

Neolog Judaism is unique to Hungary and Slovakia, comparable to Conservative Judaism in the United States but with a strong local character.

Traditional but flexible: Neolog communities uphold Jewish law but allow certain modern adaptations.

Hungarian-language sermons: Unlike Orthodox services, where Hebrew dominates, Neolog rabbis often deliver sermons in Hungarian.

Organ music and choirs: Many Neolog synagogues feature musical instruments and choirs, elements traditionally avoided in Orthodox services.

The Status Quo Ante is the middle path (Latin for “state as it was before”) movement emerged as a reaction to the Neolog-Orthodox divide, choosing to remain independent.

Moderate approach: Status Quo Ante synagogues combine elements of both Neolog and Orthodox Judaism.

More traditional than Neolog, less strict than Orthodox: While Status Quo Ante communities uphold traditional Jewish practices, they are often more flexible than their Orthodox counterparts.

Maintaining Hungarian Jewish traditions: These communities focus on preserving local Jewish customs, rather than aligning with broader European Jewish movements.

Hungary’s Orthodox Jewish community has remained steadfast in preserving traditional Jewish law (halacha). In contrast to the Neologs, Orthodox Jews in Budapest have maintained separate communities, schools, and synagogues that strictly follow Jewish law.

Strict adherence to halacha: Orthodox Jews observe all aspects of Jewish law, including kashrut (kosher dietary laws) and Shabbat restrictions.

Yiddish and Hebrew in daily life: Many Orthodox Jews, particularly within Hasidic communities, speak Yiddish or Hebrew rather than Hungarian.

Gender separation in worship: Orthodox synagogues maintain a strict separation between men and women, with women sitting in a separate balcony or behind a partition.

Now, with this rich context in mind, we invite you to step into the heart of Budapest’s historic Jewish Quarter. What follows is a thematic walking tour that will guide you through the streets of District VII, uncovering layers of heritage through synagogues, memorials, kosher eateries, cultural sites, and hidden corners that bring the past—and present—to life.

Start your tour at Deák tér

Photo: OWL.hu – Lőrincz Géza

Armored with knowledge, now that you got a little background on the history of the Hungarian Jews, it is time to start our tour! The meeting point is at Deák tér, the literal center of the city. It is easy to get here, most of the public transportation junction here. Use Metro line 1,2,3 for a quicker journey. This area used to be the open market during late medieval times. Now, here is the catch! Remember how we mentioned earlier that in the late 17th century Jewish people were expelled from the Buda side? This is the reason why they moved to the former outskirts of Pest, outside the city walls close to the market, where they could make deals. Ironically this settlement, now the Jewish district, or district 7 is the very heart of the downtown. From Deák tér you should start walking on Károly krt. Toward Madách tér, the building depicted below.

Madách tér: the gateway to Budapest’s 7th district

Photo: infostart.hu

Madách tér, located at the entrance to Budapest’s lively 7th district, is a unique and historically significant square. Framed by the grand Madách Houses, which were built in the 1930s in an Art Deco-inspired style, the square serves as a symbolic gateway to the Jewish Quarter and the famous Gozsdu Udvar. Originally envisioned as the beginning of a grand boulevard that was never completed, Madách tér today is a bustling meeting point, featuring cafés, restaurants, and cultural spaces. With its iconic archway and vibrant atmosphere, it is a popular spot for both locals and tourists exploring the historic and nightlife-rich district of Erzsébetváros. Complete with a Sisi statue (as this district was named after her) marking both figuratively and literally the front side of Erzsébet város. After taking some pictures, proceed under the archway and at the 2nd side street turn right. You will see the façade of a Synagogue.

The Rumbach Sebestyén street Synagogue: a restored architectural gem

Photo: MTI/Mohai Balázs

The Rumbach Sebestyén Street Synagogue, often called the Rumbach Synagogue, was built in 1872 and designed by the famous Austrian architect Otto Wagner. Unlike the other two synagogues, it followed a more liberal approach to Jewish worship and originally catered to a Status Quo Ante community, which aimed to remain neutral in the divide between Orthodox and Neolog Judaism.

The Rumbach Synagogue is a masterpiece of Moorish Revival architecture, inspired by Islamic designs from Spain and North Africa. The exterior features intricate arabesques, colorful brickwork, and domed towers, while the interior is adorned with ornate geometric patterns, gold accents, and an octagonal prayer hall.

During World War II, the synagogue fell into disuse and was later used as a warehouse and office space during the communist era. For decades, it remained in a dilapidated state, its magnificent interior hidden beneath layers of decay.

In recent years, extensive restoration efforts have transformed the synagogue into a cultural space, reopening in 2021 as a museum and event venue. While it no longer functions as an active place of worship, it now hosts concerts, exhibitions, and educational programs that celebrate Jewish culture and history. Continue on this street until the next intersection and turn left for a small detour. You will see the next image at the wall on Dob utca.

Carl Lutz memorial: a diplomat who defied the Nazis – The story of Carl Lutz

Photo: placemania.sk

The Carl Lutz Memorial, located in a small courtyard on Dob Street, honors Carl Lutz, a Swiss diplomat who saved over 60,000 Hungarian Jews during World War II.

As the Swiss Vice-Consul in Budapest, Lutz issued protective letters, placing Jews under the protection of neutral Switzerland. Working alongside Raoul Wallenberg and other brave diplomats, he arranged for thousands of Jews to be housed in safe buildings throughout the city.

Unveiled in 1991, the memorial features a bronze figure trapped under a glass wall, symbolizing the oppression and suffering of Hungarian Jews. The hand reaching upwards represents the hope and courage that Lutz provided during one of Budapest’s darkest periods.

Tucked away in the former Jewish Ghetto, the Carl Lutz Memorial is a hidden yet deeply moving tribute to a man who risked everything to save innocent lives. Now walk back a few steps to the intersection before this monument. Turn left and you will see a fenced building with a metal tree-like object. Walk towards it. That is the Tree of Life memorial nestled within the garden of the great Synagogue. Start walking to the right if you want to see the front façade, which looks like this…

The Dohány street Synagogue: Europe’s largest synagogue

Photo: utazások

The Dohány Street Synagogue, also known as the Great Synagogue, is the largest synagogue in Europe and the second largest in the world. Built between 1854 and 1859 in a stunning Moorish Revival style, the synagogue was designed by Ludwig Förster, who drew inspiration from Islamic architecture, particularly from North African and Spanish influences. (The truth is the architect did not really know how a Synagogue looked like, what were the architectural norms for such a building so included Islamic and even Christian elements as well during the building)

Above the entrance you can read the inscription in hebrew: ”Make me a sanctuary; that I shall dwell among them”

The synagogue’s grand facade, featuring red and yellow brickwork with decorative arches, and its twin 43-meter-high towers, crowned with onion-shaped domes, make it one of Budapest’s most iconic landmarks. The interior is equally breathtaking, with its gilded ceiling, intricate woodwork, and a massive organ—a unique feature in synagogues. The organ was played by famous musicians, including Franz Liszt.

Beyond its architectural beauty, the Dohány Street Synagogue holds deep historical significance. During World War II, the synagogue was part of the Budapest Ghetto, where thousands of Jews were forced to live under inhumane conditions. The courtyard now serves as a Jewish cemetery, an unusual feature for a synagogue, as Jewish tradition typically places cemeteries outside of city areas. The site includes the Raoul Wallenberg Memorial Park, featuring the Tree of Life, a weeping willow sculpture engraved with the names of identified Holocaust victims on the leaves.

Adjacent to the synagogue is the Hungarian Jewish Museum, which showcases artifacts, religious objects, and documents illustrating the rich history of Hungarian Jewry. Visitors can explore exhibits on Jewish traditions, famous Hungarian Jews, and the tragic events of the Holocaust.

We strongly suggest visiting the Synagogue, undoubtedly it is a must see for any tourist visiting Budapest. However, there is always a long queue, so be sure to book your ticket online and make sure you have a line skip option.

If you’ve decided to carry on and learn more about this district, find Wesselényi utca and start walking straight forward until the second crossing, called Kazinczy utca.

Mikveh: a ritual cleansing place for women

Photo: a mi erzsébetvárosunk

Next to the synagogue, visitors can find kosher restaurants, bakeries, and a mikveh (ritual bath), offering an authentic glimpse into Budapest’s Orthodox Jewish life. The area is also home to Jewish schools and cultural institutions, preserving religious traditions for future generations.

The Mikveh at 16 Kazinczy utca in Budapest is a significant institution within the city’s Orthodox Jewish community. Constructed in 1928 under the auspices of the Autonomous Orthodox Jewish Community of Hungary, it remains the only operational mikveh in Budapest today.

Designed in the Art Deco style to complement the nearby Kazinczy Street Synagogue, the mikveh’s structure incorporates both rainwater collected from the building’s roof and spring water from a borehole in the courtyard, adhering to traditional requirements for “living water” in ritual purification. The facility includes separate sections for men and women, as well as a dedicated area for the immersion of kitchen utensils, reflecting the diverse applications of ritual purification in Jewish practice. The women’s section underwent a comprehensive renovation in 2004, enhancing its facilities while preserving its historical character.

Situated behind the synagogue complex, the mikveh is part of a broader religious and cultural hub that includes a synagogue, school, and community offices. Its continued operation underscores the enduring presence and traditions of Orthodox Judaism in Budapest.

After checking out this building start walking back to Wesselényi utca. Stay on Kazincy street and in a few minutes, you will bump into the Orthodox Synagogue.

The Kazinczy street Synagogue: the heart of Orthodox Jewish lifen

Photo: index.hu

The Kazinczy Street Synagogue, located in the same historic Jewish Quarter, represents the Orthodox Jewish community in Budapest. Built in 1913, it is a masterpiece of Hungarian Art Nouveau architecture, designed by architects Sándor and Béla Löffler.

The synagogue’s distinctive façade features colorful ceramic tiles, geometric patterns, and intricate carvings, making it a standout example of Secessionist (Art Nouveau) architecture. Inside, the lavish blue and gold decorations, stained glass windows, and wooden furnishings create a warm and spiritual atmosphere.

Unlike the Neolog (more modernized) congregation of the Dohány Street Synagogue, the Kazinczy Street Synagogue serves Budapest’s Orthodox Jewish community. It adheres to traditional Jewish customs, with separate seating for men and women, a focus on kosher dietary laws, and daily prayer services. Next to the synagogue, visitors can find kosher restaurants, bakeries, and a mikveh (ritual bath), offering an authentic glimpse into Budapest’s Orthodox Jewish life. The area is also home to Jewish schools and cultural institutions, preserving religious traditions for future generations.

The Mikveh at 16 Kazinczy Street in Budapest is a significant institution within the city’s Orthodox Jewish community. Constructed in 1928 under the auspices of the Autonomous Orthodox Jewish Community of Hungary, it remains the only operational mikveh in Budapest today.

Designed in the Art Deco style to complement the nearby Kazinczy Street Synagogue, the mikveh’s structure incorporates both rainwater collected from the building’s roof and spring water from a borehole in the courtyard, adhering to traditional requirements for “living water” in ritual purification.

The facility includes separate sections for men and women, as well as a dedicated area for the immersion of kitchen utensils, reflecting the diverse applications of ritual purification in Jewish practice. The women’s section underwent a comprehensive renovation in 2004, enhancing its facilities while preserving its historical character. After passing some Kosher cafés and restaurants, at the next intersection (Dob utca) turn left until you reach a busy gate labeled as Gozsdu Udvar.

Gozsdu Udvar: The passage of surprises

Photo: kettosmerce.blog.hu

Located in the heart of Budapest’s Jewish Quarter, Gozsdu Udvar is one of the city’s most iconic and lively destinations. This unique passage, stretching between Dob Street and Király Street, is a bustling hub of restaurants, bars, cafés, and markets, making it a favourite spot for both locals and tourists. However, beyond its modern vibrancy, Gozsdu Udvar has a rich and complex history dating back to the 19th century.

The story of Gozsdu Udvar begins with its namesake, Emanoil Gojdu (1802–1870), a wealthy Romanian lawyer, businessman, and philanthropist. Born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Gozsdu was a strong advocate for the rights and education of Romanians living in Hungary. Upon his death, he left his fortune to a foundation aimed at supporting Romanian students, and part of this legacy led to the establishment of the Gozsdu Courtyard in 1901.

The complex was designed by architect Győző Czigler and originally functioned as a series of interconnected residential buildings and commercial spaces. It quickly became an integral part of the Jewish Quarter, home to artisans, shopkeepers, and families, reflecting the multicultural nature of Budapest at the time. Reopened in 2008, Gozsdu Udvar has transformed into one of Budapest’s most popular entertainment districts. The passage is lined with stylish bars, restaurants, cafés, and galleries, offering a dynamic mix of Hungarian and international cuisine, live music, and a vibrant nightlife scene. On weekends, Gozsdu Market attracts crowds with its handmade crafts, vintage clothing, artwork, and antique items, making it a great place to explore local creativity. Additionally, the Jewish heritage of the area is still present, with cultural events and exhibitions that celebrate the rich history of the district.

After walking through this passage you will wind up on Király utca. Start walking to the right until you reach number 15. The gate will be (hopefully) open and walk in the buildings courtyard, where you will find another passage with a wall at the end of it.

Photo: Pitz Dániel/Startlap

One of the few tangible remnants of the ghetto’s physical barriers was in the courtyard of a building at Király utca 15. Originally an old stone wall topped with barbed wire, it served as part of the ghetto’s perimeter during its brief existence. Unfortunately, this original section was demolished in 2006 during construction work. Recognizing its historical significance, a memorial wall was erected in 2008 using some of the original materials, though it does not precisely replicate the original structure. This reconstructed wall now stands as a silent witness to the atrocities endured by the Jewish community during the Holocaust. Ever since 2010 this sight is considered to be an official Holocaust memorial.

This is the official end of the tour, however there are more sights to keep an eye out for. If you are tired a bit, here are some traditional, Hungarian and Glatt Kosher restaurants, which you passed by.

Carmel Restaurant: Elegant kosher dining on Kazinczy street

Photo: 7.kerulet ittlakunk

Established over 30 years ago, Carmel Restaurant stands as a pillar of kosher dining in Budapest. Located in the heart of the Jewish Quarter, it seamlessly blends traditional Hungarian and Jewish culinary traditions. The menu features classic dishes such as goulash, schnitzel, and stuffed cabbage, alongside Israeli salads and other specialties. The restaurant’s elegant ambiance and commitment to quality make it a favourite among both locals and tourists. Carmel also offers Shabbat meals, which should be reserved in advance.

Tel Aviv Café: Kosher dairy, and pizza dining in the heart of Budapest

Photo: Tel Aviv Café Facebook page

Located directly across from the Kazinczy Street Synagogue, Tel Aviv Café offers a cozy atmosphere with a menu that includes a variety of dairy dishes. Patrons can enjoy items such as pizza, pasta, fish, salads, and Israeli-style breakfasts. The café is also known for its take-away services, providing convenient options for travellers, including pre-packaged sandwiches suitable for early flights.

After some nice meals, if you are ready to continue you must either reach the closest Metro 2 stop (M2 -redline) and head towards the Kossuth tér. You might recognise this stop from earlier, as this is where the Parliament is at. When you exit from the Metro, walk left until embankment of the Danube. There walk a bit South or turn left and walk along the promenade. That is where you will find the Shoes Memorial..

Shoes on the Danube: a haunting Holocaust Memorial

Photo: Silverline Cruises

One of Budapest’s most powerful Holocaust memorials, the Shoes on the Danube, was created by sculptor Gyula Pauer and filmmaker Can Togay in 2005.

This moving installation consists of 60 pairs of iron-cast shoes, representing the thousands of Jewish men, women, and children executed along the Danube by the fascist Arrow Cross Party in the winter of 1944–1945.

Victims were forced to remove their shoes before being shot, their bodies falling into the river. Today, the site stands as a stark reminder of the Holocaust, often adorned with candles, flowers, and pebbles, placed there by visitors paying their respects.

Located on the Pest side of the Danube, near the Hungarian Parliament, this solemn yet powerful memorial is a must-visit for those wishing to reflect on the darkest chapter of Hungary’s history.

From here you can decide to visit the Glass House which is a couple of blocks away. Try to exit the embankment area by using any stairs or roads. We suggest that you walk back towards the Parliament from where you approached this monument, so that you pass the Szabadság tér. Walk pass it diagonally until you reach Vadász utca which runs parallel to the aforementioned Szabadság tér. Under number 29 you will find a plaque and a small memorial house which can tell you the story of the…

“The Glass House” – A factory where lives were saved

Photo: Silverline Cruises

Nestled in Budapest’s 5th District at Vadász utca 29, the Glass House (Üvegház) stands as a poignant testament to courage and humanitarianism during one of history’s darkest periods. Originally constructed in the 1930s as a modernist glass factory and showroom for the Weiss family, the building’s sleek design, featuring extensive glass elements, lent it the moniker “Glass House.” However, its legacy was forever transformed during the Holocaust, when it became a sanctuary for thousands of Jews seeking refuge from persecution.

Recognizing the historical significance of the Glass House, the Carl Lutz Foundation established a Memorial Room in 2005 within the building’s former garage. This space now serves as a museum, displaying photographs, documents, and personal testimonies that chronicle the heroic efforts undertaken within these walls. To see the last suggested sight on our list be sure to turn right on Vadász utca and walk toward Arany János Utca Metro station. Take M3 (Blue metro) until Corvin Negyed station and once you exited, follow the signs toward the Holocaoust Museum.

Bét Élijáhu: Synagogue and a holocaust memorial at Páva streetd

Photo: Misibacsi – Wikipedia

The Holocaust Memorial Center and Synagogue on Páva Street in the 9th district, stands as a poignant testament to Hungary’s commitment to remembering the atrocities of the Holocaust and educating future generations. Established by the Hungarian government in 1999, it is one of the few state-founded institutions worldwide dedicated solely to Holocaust research and education. The center’s permanent exhibition, “From Deprivation of Rights to Genocide,” chronicles the systematic persecution of Hungarian Jews from 1938 onwards, culminating in their deportation to extermination camps. Interactive displays, personal testimonies, and historical artifacts provide an immersive educational experience.

In the courtyard, the Memorial Wall bears the names of over 150,000 identified victims, engraved into glass panels. Adjacent to it, the Tower of Lost Communities commemorates 1,441 Hungarian settlements whose Jewish populations were annihilated during the Holocaust.

Whatch out! Look down for a moment and read: Stumbling stones

Photo: jewishwalks.hu

For our last entry there is no specific location these are scattered all over the city, albeit you must be a little bit more of a careful observer to spot the so-called Stumbling Stones.

The Stolpersteine initiative was conceived by German artist Gunter Demnig in the early 1990s. His vision was to commemorate victims of Nazi oppression—Jews, Roma, political dissidents, LGBTQ+ individuals, and others—by embedding personalized brass plaques into the pavements outside their last chosen residences. Each plaque begins with “Here lived,” followed by the individual’s name, birth year, fate, and, if known, the date and place of death. This decentralized form of remembrance transforms everyday spaces into sites of reflection, ensuring that the memories of these individuals remain woven into the fabric of daily life.

The Stolpersteine serve as intimate memorials, grounding the vast tragedy of the Holocaust in personal narratives. By situating these plaques in front of former residences, they restore individuality to the victims, reminding us that history is composed of countless personal stories.

In Budapest, these stones not only honour the memory of those lost but also educate residents and visitors about the city’s complex history. They stand as silent witnesses, urging us to remember and reflect upon the past to inform a more compassionate future.

Well, this was it! We hope that you appreciate our effort to collect you the most interesting cultural sites within Budapest. Hope you find it educational, and intriguing.

Whether you’re exploring your own heritage, deepening your historical understanding, or simply discovering the soul of the city through its Jewish legacy, this tour offers a meaningful and unforgettable journey.

We hope this suggested route by Purpleliner Budapest has helped guide your steps through both the well-known landmarks and the quiet corners of Budapest’s Jewish past and present. May your visit be as enlightening as it is inspiring.

If you found our article helpful in any way, please give us a like, rate us on any preferred platform.

L’shanah tovah – and happy exploring!